Summary

We implemented a fluid simulation on a CPU with OpenMP and on a GPU with CUDA from scratch, and compared the performance of the two implementations. The fluid responds to mouse interactions, and renders a display using OpenGL.

Demo

Background

The simulation of fluids is computationally very expensive, and could benefit greatly from paralellization since many computations are being done for every pixel.

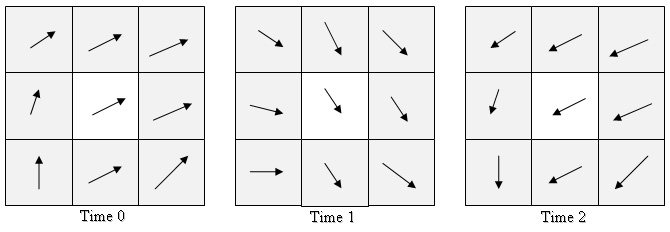

In a grid-based simulation like ours, the fluid is represented by dividing up the space a fluid might occupy into individual cells (in our case, pixels), and storing certain quantities of the fluid for each cell, like velocity, pressure, and color. These different quantities represent the fluid and are updated during every time step. Each quantity is represented in a separate array.

A grid-based representation with a single quantity (velocity, for example)

A fundamental operation in grid-based fluid simulations is advection, which is moving quantities around the grid for the next time step based on the current velocity of each cell. Simplified, forward advection is calculating where the fluid in your cell will be at the next time step, and giving your current value of the quantity that you're advecting (velocity or color) to the cell where the fluid will be. Backwards advection is trickier to understand, but it's essentially the same idea except you trace your velocity backwards and pull that value into your cell. Additionally, there are other operations to create realistic fluid motion, accounting for vorticity (rotation), divergence, pressure, and color.

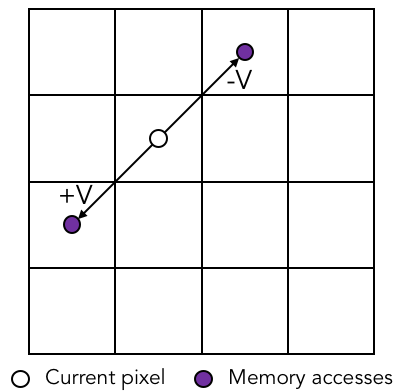

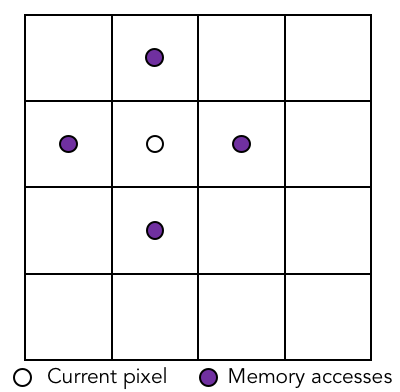

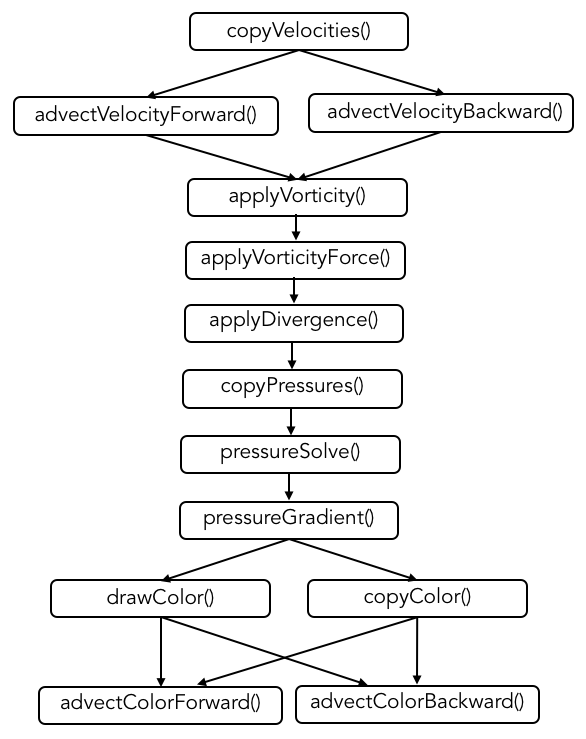

We can use parallelization within each of these computations to perform the operations on each cell in parallel. However, due to the nature of fluid motion, the state of a cell is affected by nearby cells, so these operations require accessing quantities from cells other than your own cell. This introduces a level of complexity - because the dependencies depend on the velocity of the cell, operations have to be fully completed for the entire grid in order to move on to the next operation.

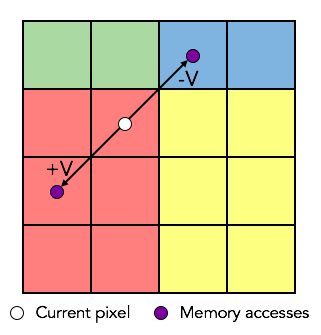

In advection, the computation for a cell loads/stores quantities from other cells

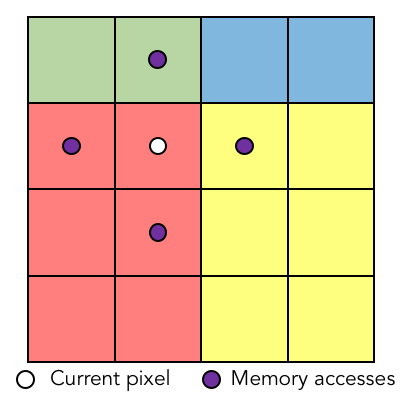

In the operations from applyVorticity() to pressureGradient(), quantities from neighboring cells are used

Dependency graph for our implementation

At the end of each time step, the appropriate color for each pixel is given to OpenGL to render onto the screen. The faster the computation is, the faster each frame is able to be rendered, which creates a more seamless animation.

Approach

We used CUDA to map the computation onto the GPU. Specifically, we copied all the arrays into device memory and translated each operation into a kernel, which we called for each grid cell using 16x16 thread blocks. Because of the dependencies (where a cell relies on the values of nearby cells), we had to separate kernel instances for each operation in order to synchronize before moving on to the next operation.

One area that we put special thought into was processing the mouse press events. In each screen render, for every pixel, we need to go through every new mouse segment (between two consecutive mouse presses since the last render). We considered the tradeoffs between launching a kernel for each pixel that looped through each mouse segment, or flattening it and having a thread for each pixel-segment pair. We figured that since the number of segments would likely be small (usually less than 50) compared to the number of pixels in the image, it would be better to have a kernel call with a loop for each pixel. This would have less kernel launch overhead and less communication between threads in a thread block, since the purpose of looping was to find the pixel's minimum length to any of the mouse segments. In the flattened version, the threads in a thread block would have needed to communicate with each other to determine what the minimum length was.

Simply translating the implementation to CUDA kernels improved the computation time drastically. Next, we decided to take advantage of shared memory in a thread block to achieve further speedup. Each thread block performs computation on a block of pixels on the screen. For both advection and the operations that access a pixel's immediate neighbors, it is highly likely that the other cells being read from or written to will be in the block, and thus will be computed by threads in the same thread block. Only pixels along the perimeter or pixels with large velocities will have to access global device memory for quantities of cells outside of the thread block.

Advection within and outside a thread block

Looking at a pixel's direct neighbors will mostly use shared memory, except on the perimeter of a block

Results

One of our concerns throughout the project was to make a simulation that looked realistic. We didn't want to end up parallelizing something completely useless, so we put a lot of effort into our baseline implementation. After struggling through some unfamiliar physics and fluid mechanics, we are pretty proud of the visual aspect of our project.

To evaluate the performance of our implementations, we ran on the GHC machines. The machines each contain an 8 core 3.2 GHz Intel Core i7 processor and an NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1080 GPU.

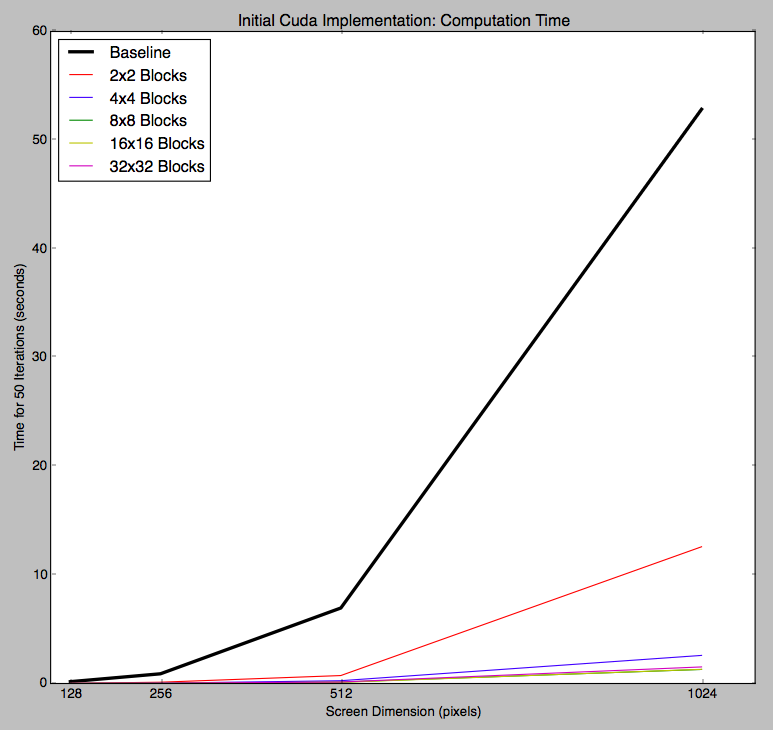

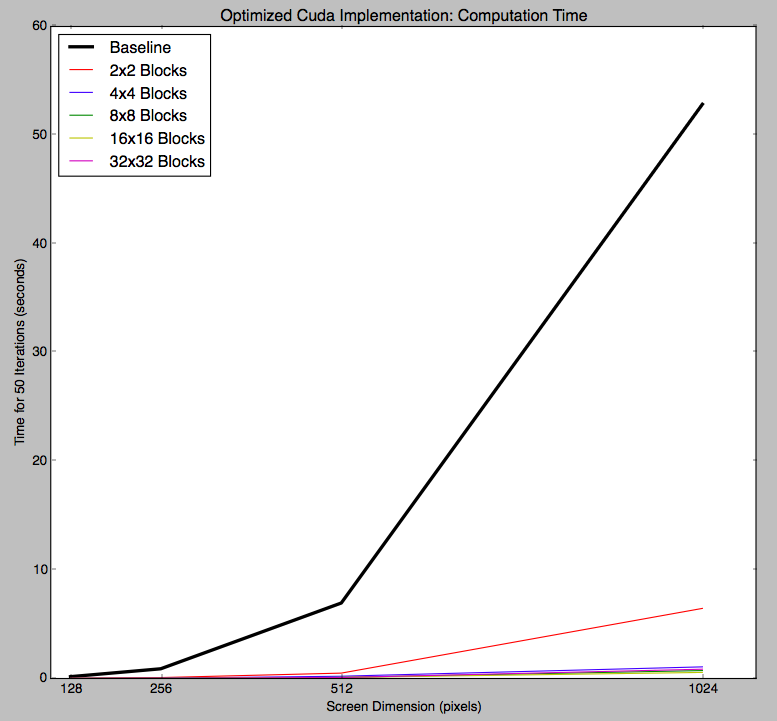

Our initial parallel implementation involved converting all of the functions from our baseline into CUDA kernels so that the computations could be done in parallel on the GPU. We were pleased with the results. For just the computation portion, our GPU implementation achieved around 35x speedup over the baseline CPU implementation. The graph below shows the time spent doing computation for the pixels with our baseline implementation and our CUDA implementation (with different block sizes) for a various screen sizes.

Obviously, the graph is upward trending since the larger screens have more pixels and require more computation. In general, we see that the use of thread blocks in CUDA increases performance because it supports work being done in parallel. Additionally, on modern NVIDIA hardware, groups of 32 CUDA threads in a thread block are executed simultaneously using 32-wide SIMD execution. This explains why the 2x2 and 4x4 thread blocks achieves less speedup - with only 4 or 16 threads, there are empty, unused SIMD vector lanes.

Computation time for 50 iterations of various screen sizes, using our initial CUDA implementation

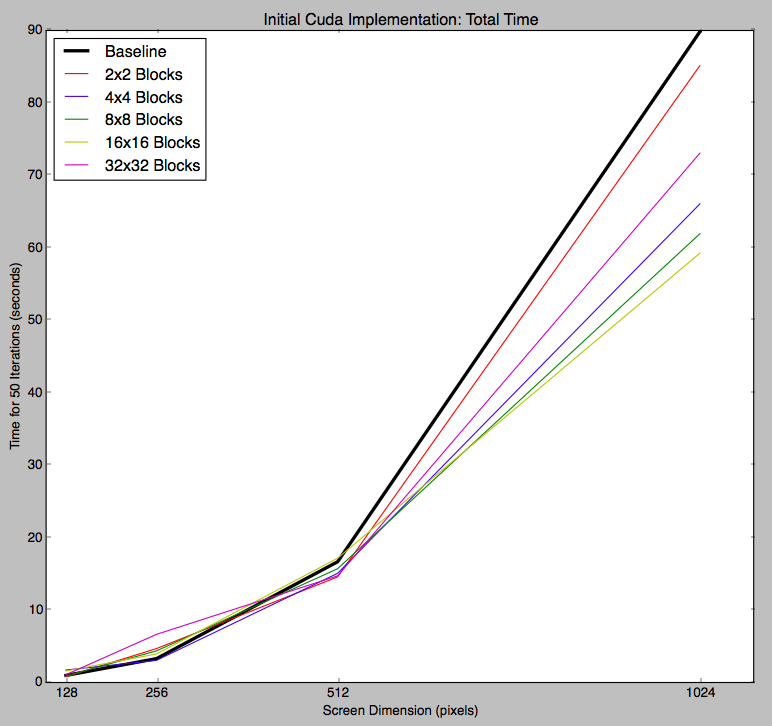

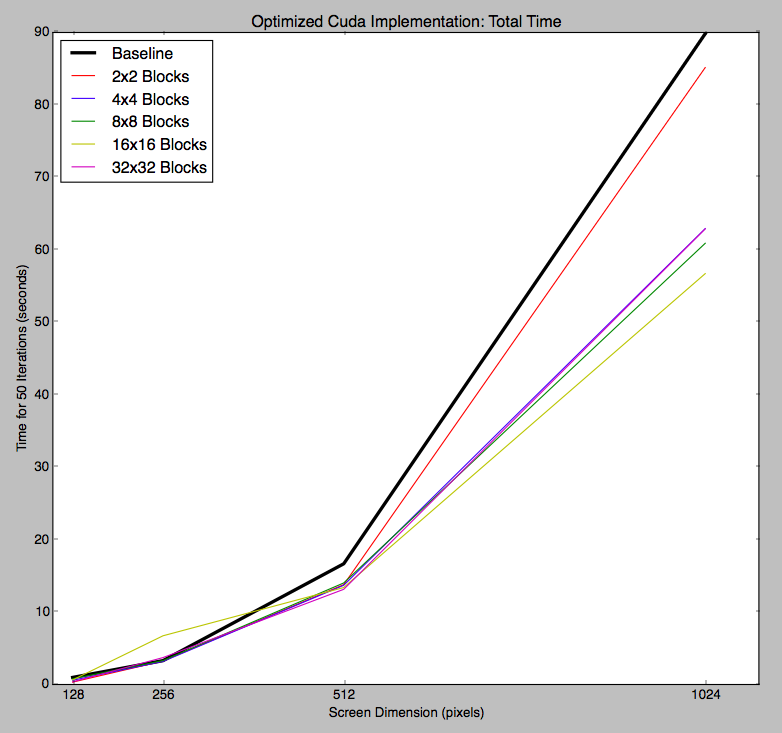

Although this initial parallel implementation achieved impressive speedup over our baseline during the phase where the computation for each pixel is done, we noticed that the overall time was not significantly faster. The graph below shows the total time to run 50 iterations, for our baseline and CUDA implementations with different block sizes. When considering the entire program (computation and visual rendering), our initial parallel GPU implementation achieved only around 1.5x speedup over the CPU implementation.

Total time for 50 iterations of various screen sizes, using our initial CUDA implementation

This suggested to us that the actual drawing of the pixels in the display was a time consuming portion of our program. Online research confirmed that the glDrawPixels function is generally slow. We spent two full days trying to figure out how to render to a CUDA surface object (to be stored in GPU memory) which could be bound to a texture and displayed more efficiently with openGL. We tried our best and followed various examples from the internet, but we were ultimately unable to figure it out. We decided it would be more productive for us to continue optimizing the computational portion of the program, where we would be able to apply more topics from the course.

The first major change we made to our parallel implementation was to take advantage of thread block shared memory. Loading data into the shared memory of a thread block allows it to be accessed quickly for computation later, since the latency is significantly lower for accessing shared memory than uncached global memory. In each kernel launch, we have a thread corresponding to each pixel in our display window. So, at the start of a kernel, each thread can load the data for its corresponding pixel into a shared memory array. After calling __syncthreads(), we ensure that all threads in the block have loaded their data. Then, as we proceed with the computation of the kernel, most of the required memory accesses will have already been loaded into shared memory, so they can happen very quickly.

We first noticed the opportunity to take advantage of shared memory in the kernels with computations that require the values of the top, bottom, left, and right neighboring pixels of the current pixel. Each thread block corresponds to a square of pixels in the display, so a pixel's neighbors are likely to be in the same block. Consider a kernel that requires the pressures of the neighboring pixels, for example. First all the threads in the block cooperatively work to load the pressures of the corresponding pixels, with each thread loading one value. Once all the data is loaded into shared memory, each thread performs the computation involving its neighbors. If a neighbor is in the same block, the thread looks up the pressure from the shared array. In the few cases were a pixel's neighbor is outside of the block, the thread looks it up from global memory. This access is still slow, but there are relatively few of them.

We also noticed that shared memory could help in the advect forward and backward kernels for both velocity and color. During advection, a pixel is assigned a new value based on the value of a pixel nearby, which is likely in the same block. So, preloading all the values into shared memory before advecting increases the number of memory accesses that can be serviced by shared memory rather than global memory, which is slower.

Additionally, in our initial CUDA implementation, we called cudaDeviceSynchronize() after every kernel call. This was to respect the sequential nature of the computation, where each computation relies on the results of the previous computation. However, when optimizing we realized that we could get away with removing some of the synchronization and still display a realistic simulation. Specifically, we removed the cudaDeviceSynchronize() between advecting forward and backward (for both velocity and color). With this relaxation of the dependencies, it is possible that two threads will write a new value to the same pixel and only one will be recorded. However, pixel perfect accuracy is not required to achieve a reasonable simulation. Removing the extra synchronization means that resources need not be idle between these steps. We acknowledge that this modification is something we can only do if we are focused on a purely aesthetic result, because it means our simulation is not technically correct.

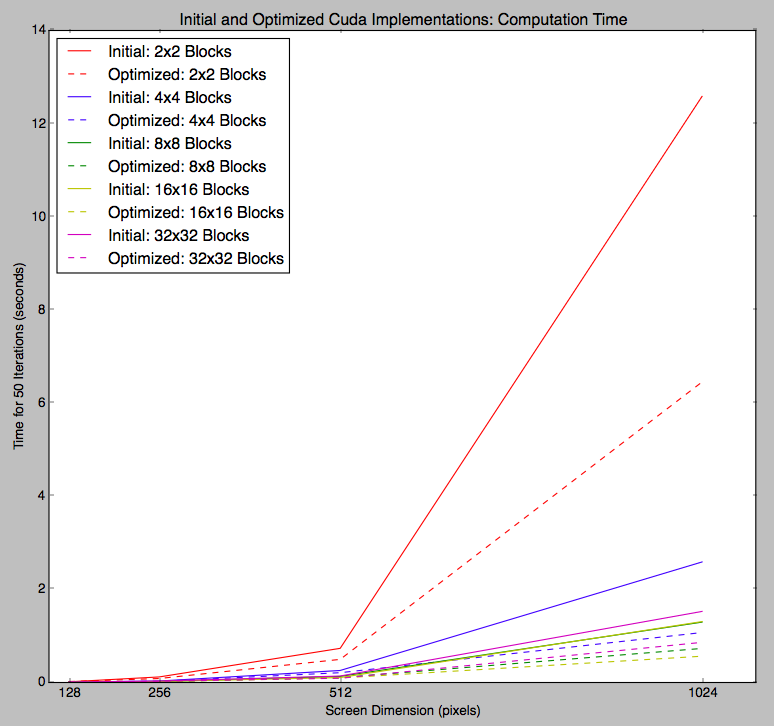

These changes improved our GPU implementation substantially. The graph below shows the computation time for the initial GPU implementation compared to the optimized GPU implementation, for various block sizes. For all block sizes, the dotted line (which represents the optimized version) is lower than the solid line (which represents the initial version). This suggests that our optimizations were effective.

Computation time for 50 iterations of various screen sizes, using initial and optimized CUDA implementations

With these changes, we improved our GPU implementation speedup over the CPU implementation for just the computation portion to around 80x, shown in the graph below.

Computation time for 50 iterations of various screen sizes, using our optimized CUDA implementation

Unfortunately, our speedup is still ultimately limited by the slow drawing. Even with our improvements, our GPU implementation still achieves around 1.5x speedup over the CPU implementation for the total time.

Total time for 50 iterations of various screen sizes, using our optimized CUDA implementation

As all of our graphs demonstrate, we experimented with different thread block sizes. Our results indicate that 16x16 thread blocks, which correspond to 16x16 pixel squares of the display, achieved the lowest times.

References

We mainly referenced Practical Fluid Mechanics and haxiomic's GPU-Fluid-Experiments to understand the physics of fluid motion.

List of Work Done by Each Student

Equal work was performed by both project members.